How comic books are becoming more accessible

Sound, tactile materials and new technologies are all being used to help bring the visual storytelling of comics to life for blind and partially sighted people

According to the Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB), around 340,000 people are registered blind or partially sighted in the UK, while more than two million people are estimated to be living with sight loss. Despite the existence of legislation that aims to protect their rights, the charity’s research suggests that blind or partially sighted people “experience a significant information and inclusion gap because of their vision impairment” and that “the accessibility of products, information and services is still not an area where people with sight loss have equality of experience”.

The act of reading has long been something that the blind community has been able to experience at a relatively higher level of equity with sighted people. Braille, the tactile reading and writing system which is 200 years old this year, has moved with the times and now features in refreshable braille displays and braille note takers – dedicated computers for braille users. Books published in braille are now often produced by specialist embossing machines that use translation software to convert the printed word into braille cells.

The publishing industry has also embraced the digital audiobook since it first emerged in the late 1990s. The current popularity of the medium means that audiobooks now exist in tandem with mainstream print publishing titles, meaning many more books have become accessible to blind and visually impaired readers. The RNIB itself offers a range of talking books and various players that incorporate the Digital Accessible Information System (DAISY), enabling searchable mp3s and bookmarking, as well as a speaking speed that can be altered without a loss of quality.

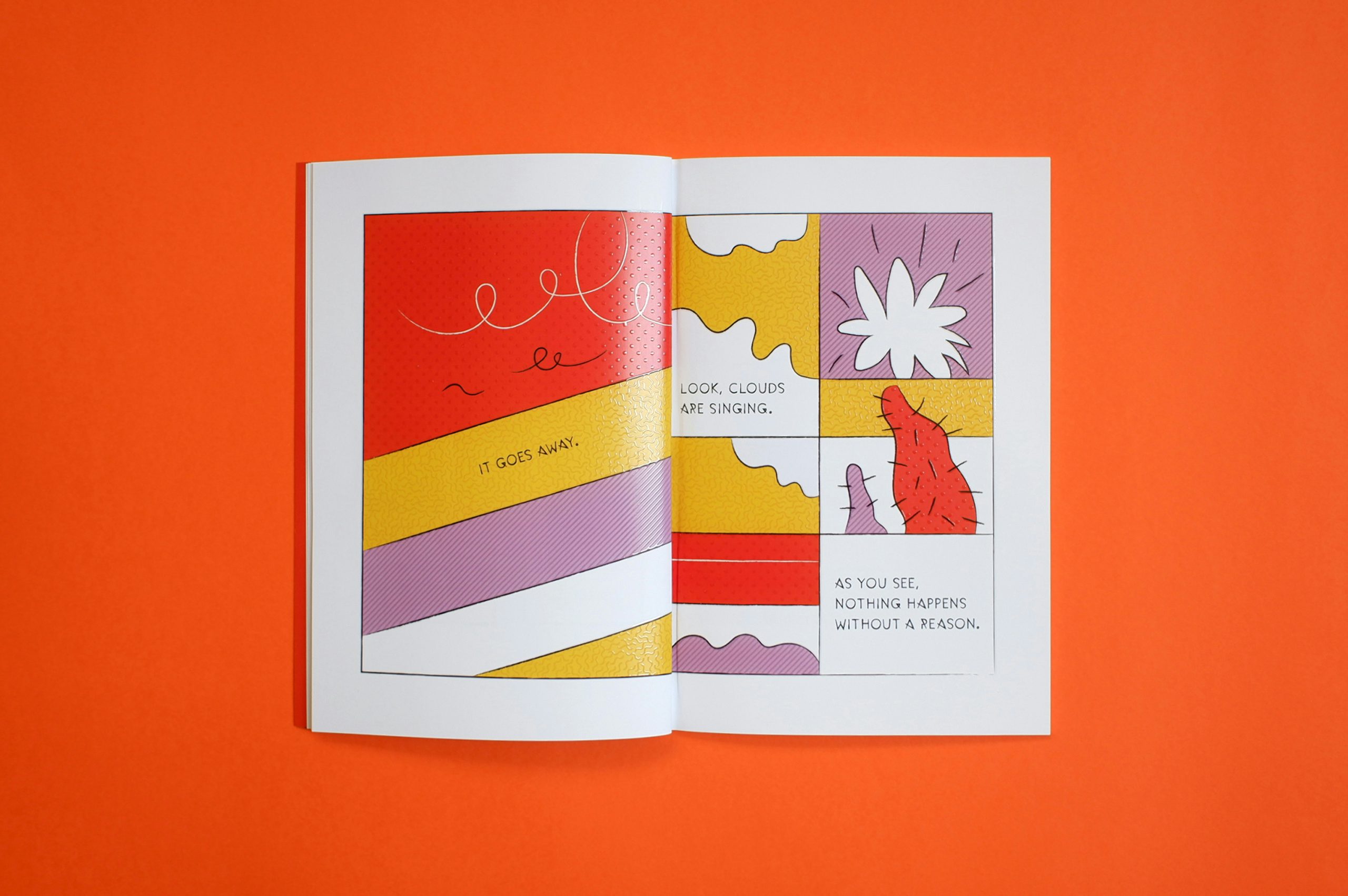

Conveying the experience of reading a comic book is much more challenging, however. As a visual medium that operates through a blending of text and image, it’s a process which makes use of dialogue, scene setting, description, narration, tone, not to mention formal experimentation. Replicating the experience of reading a comic in a non-visual way sounds almost impossible. Yet comic book artists, publishers and academics, together with a range of experts on sight loss, are routinely taking on the task of making their products more accessible to blind readers.